Nearly a quarter of the world’s zinc production is from volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) deposits. In Canada, approximately half of country’s zinc production is from VMS deposits that also supply 40% of Canada’s silver production. VMS deposits also yield significant amounts of other base metals like lead, silver, copper, and gold.

Volcanic massive sulphide deposits are accumulations of metal sulphides that precipitate from heated hydrothermal fluid associated with volcanically active under-sea environments.

Ore Minerals

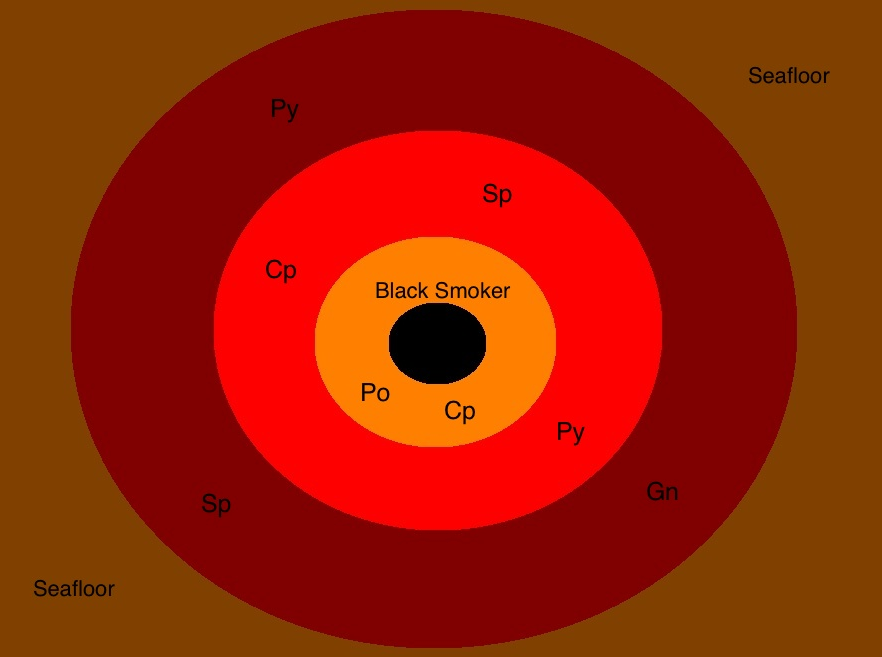

The main ore minerals in VMS deposits are sulphides, including pyrite (iron sulphide), sphalerite (zinc sulphide), chalcopyrite (copper-iron sulphide) and galena (lead sulphide).

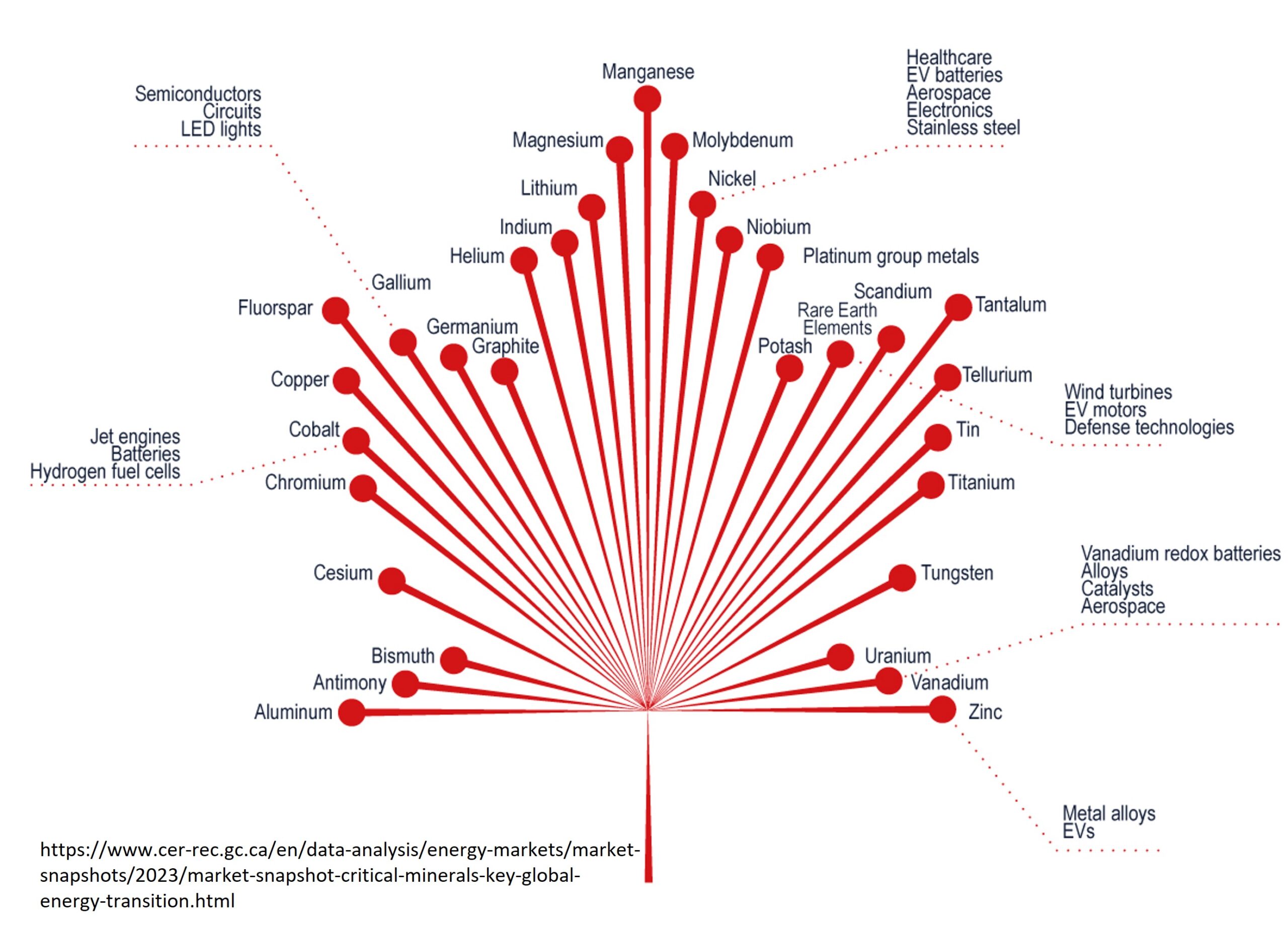

VMS deposits contain minor amounts of silver and gold plus a large variety of other elements including cobalt, tin, selenium, manganese, arsenic, tellurium, antimony, and mercury among others. Some of these can be extracted as a by-product, increasing a mine’s profitability.

Formation

Volcanic massive sulphide deposits are accumulations of metal sulphides that precipitate from heated hydrothermal fluid associated with volcanically active under-sea environments.

The volcanic activity typically occurs at extensional zones, like mid-ocean ridges, caused by rifting in the Earth’s crust. A rift is simply an area where the Earth’s crust is being pulled apart, and the result is that magma from Earth’s mantle rises up beneath the area where the crust is being stretched.

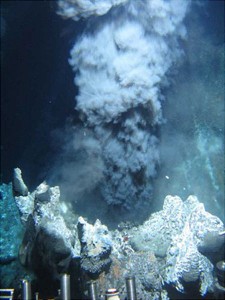

Rifting causes magma from the mantle to rise and cool in the Earth’s crust. The magma expels volatiles that carry valuable elements toward the surface. The large temperature difference between the rising volatiles and seawater percolating down through the rock causes convection. Convection allows more metals to be incorporated into the fluids until the fluids finally escape to the surface through faults or similar structures. These fluids can reach temperatures of 400°C and are expelled into the ocean via a hydrothermal vent or “black smoker”. Ocean water is as cold as 2°C and the dramatic temperature difference causes sulphide minerals to precipitate onto the seafloor. The dissolved metals precipitate out as sulphide minerals – the ore minerals that are mined in modern VMS deposits.

VMS Size, Distribution, and Geometry

The two features make VMS deposits such desirable exploration targets are their size and geometry. These deposits often form over a long time and can be reactivated on numerous occasions. This results in individual lenses that are a hundred meters thick and extend hundred meters along strike. The reactivation also causes the deposits to be zoned around the black smoker pipe, with a predictable distribution of sulphides.

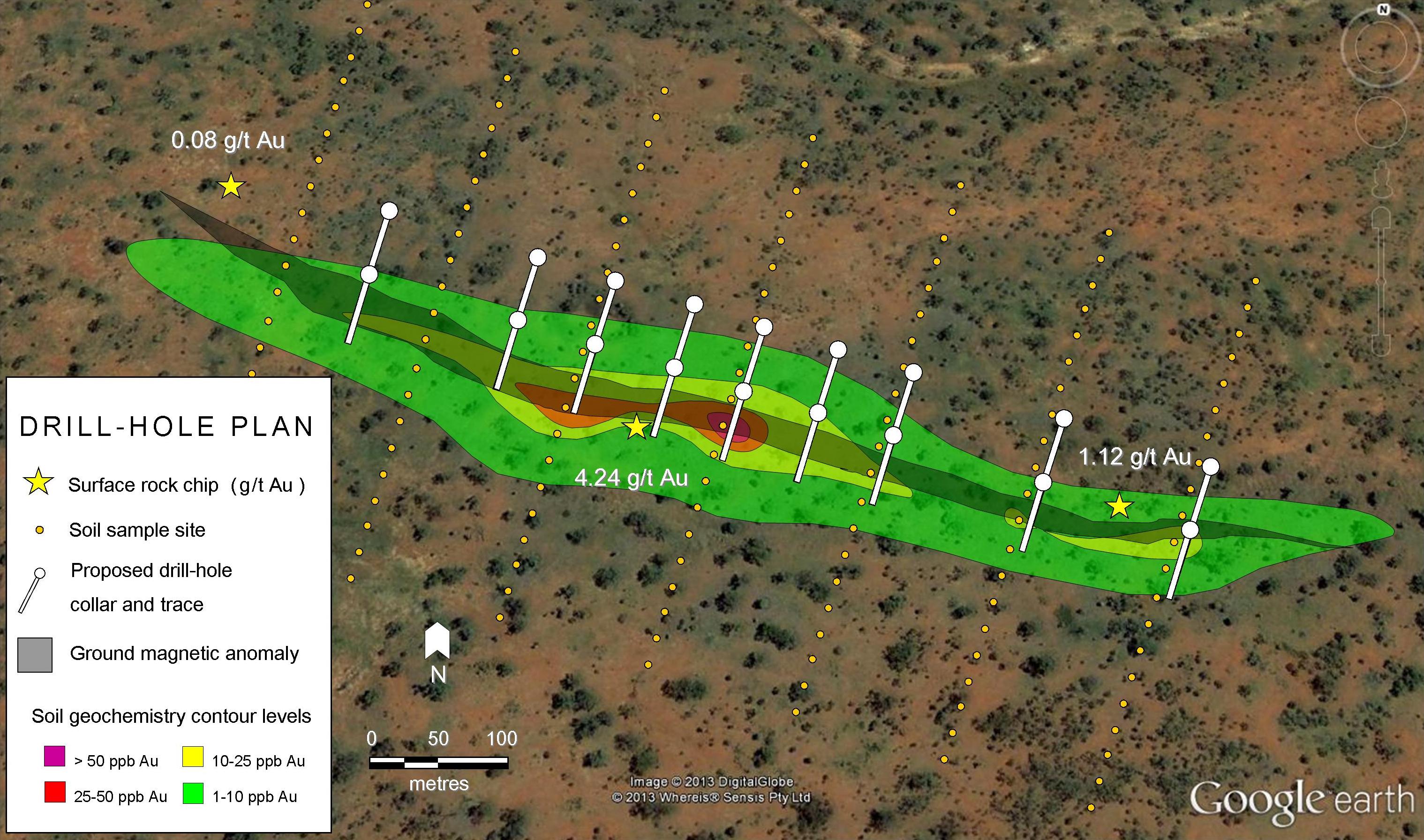

The massive accumulations of sulphides show up very well in geophysical surveys because they are both denser and more conductive than the surrounding rock, making VMS deposits a relatively easy geophysical exploration target.

The deposit shape makes VMS ideal for cheap open-pit mining methods because a large amount of ore can be removed without having to remove very much waste rock. This is a much cheaper mining method than when ore is hosted in narrow veins, which results in a much higher ratio of waste to ore removal.

VMS deposits often occur in clusters within a particularly small area (~10 km2) all related to the same event, since the metal-rich fluids may escape to the surface through many vents. The discovery of one large VMS deposit may well mean that there are other targets nearby. Examples include VMS deposits in Canada’s Bathurst Mining Camp and VMS-SEDEX hybrid deposits in Spain/Portugal’s Iberian Pyrite Belt.

Almost any age of terrain can potentially host a VMS deposit. The oldest VMS style deposits are some 3.4 billion years old while the youngest are being deposited today in oceans including the Red Sea and the western Pacific Ocean. There are ~800 VMS deposits known worldwide with about 350 of those in Canada. Worldwide there is extensive exploration for VMS-style deposits, particularly in the remote Canadian arctic.

Classification

Geologists have classified VMS deposits according to their magmatic assemblage, metal source, geodynamic setting, or type (analogue). The US Geological Survey classified VMS deposits according to their magmatic assemblage – the types of minerals that make up the rock.

- Mafic associated: VMS deposits associated with geologic settings dominated by mafic rocks, such as ophiolite sequences. Mafic rocks are igneous rocks primarily composed of dark-colored minerals rich in iron and magnesium. Examples of mafic VMS deposits include those in Cyprus and Japan (Besshi).

- Biomdal-mafic associated: VMS deposits that are dominated by mafic rocks, but include up to 25% felsic rocks (igneous rocks that are light in color and composed of minerals rich in aluminum, silicon, sodium and potassium). Examples include Urals-type VMS deposits and Flin Flon and Kidd Creek in Canada.

- Felsic associated: VMS deposits dominated by felsic rocks and siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, with less than 10% mafic rocks. Examples include the Bathurst Mining Camp and the Iberian Pyrite Belt.

Important Deposits

VMS deposits occur worldwide, in Canada, Alaska, Australia, Japan, Sweden, Portugal, Spain and the Philippines. Of the ~800 VMS deposits known worldwide, ~350 of those in Canada. Worldwide there is extensive exploration for VMS-style deposits, particularly in the remote Canadian arctic.

Bathurst Mining Camp

The Bathurst Mining Camp (BMC) is one of the world’s oldest base metal mining districts and one of Canada’s largest volcanogenic massive sulphide (VMS) deposits. Primary ore commodities include lead, zinc, copper, gold, and silver. Although mining activity in the BMC stopped in the early 2000s, there is potential for subsurface base metal deposits, particularly gold.

Flin Flon, Manitoba, Canada.

The Flin Flon Greenstone Belt are ancient Precambrian rocks which host the largest concentration of VMS deposits in Canada. The ore bodies are predominantly zinc-copper with significant gold and silver. Ore bodies range in size from 100,000 tonnes to 60 million tonnes.

One of the largest producers is Hudbay Minerals Inc., which was founded in 1927 to mine the region. Their 777 Mine produces zinc, copper, gold and silver, which final production expected in 2022. They are currently developing a new project at Snow Lake some 215km north of Flin Flon. This project is called the Lalor Mine and is expected to be complete in 2022. In 2019 their production figures included:

- 23,354 tonnes copper

- 119,106 tonnes zinc

- 110,406 ounces of silver and gold

Kidd Mine, Timmins, Ontario, Canada

The mine is hosted in the 2.8 – 2.6 billion year old Abitibi greenstone belt in Ontario, Canada. The Kidd Mine is operated by Glencore’s Kidd Operations and is one of the world’s deepest base metal mines, with current mining greater than 9,600 feet underground. Opened as an open pit mine in the 1960s, the mine is expected to close in 2022.The main commodities are copper and zinc.

List of Companies Mentioned

Further Reading

- USGS Volcanogenic Massive Sulfide Deposits of the World (article)

Subscribe for Email Updates