The combination of heat and water is what creates most mineral deposits. Aside from the weathering processes that subsequently transport (placer or alluvial deposits) or concentrate the minerals in place (laterites), most mineral deposits are associated with water and heat either at shallow depths, or deep under the earth’s crust.

The Importance of Hot Water

Most of us who have stirred sugar into hot coffee, or made candy, understand that heating water will allow it to dissolve more of an additive like sugar or metals. Heated groundwater concentrates valuable minerals, particularly tin, copper, gold, and silver. Water circulation is caused by changes in temperature initiated by tectonic activity or volcanic eruptions. As the conditions change the minerals may precipitate (solidify) along faults and surrounding rocks.

Those changing conditions involve:

- Temperature or pressure decreases

- Reaction with wall-rocks, particularly mafic and carbonate rocks

- Degassing

The water, which is critical for the process, comes from a variety of sources including:

- Ground water

- Sea water, for underwater hydrothermal activity

- Dewatering of metamorphic rocks

- Dewatering of buried and compressed sediments

- Water released from melting rock

The heat, which drives the process, comes from:

- Heat from the mantle (inner layer of the Earth)

- Rising of magma into shallower crustal rocks

- Radioactive heat from cooling masses of intrusive rocks

Types of Hydrothermal Deposits

Different types of hydrothermal deposits occur depending the on the geological setting.

Rising Fluid Deposits

As hydrothermal fluids rise they can result in:

- Porphyry copper deposits, which form at temperatures of 200-800C, at moderate depths

- Cordilleran veins, which form at intermediate to shallow depths;

- Epithermal gold and other metal deposits, which form at temperatures of 50-300C, at shallow depths.

Circulated Fluid in the Magma

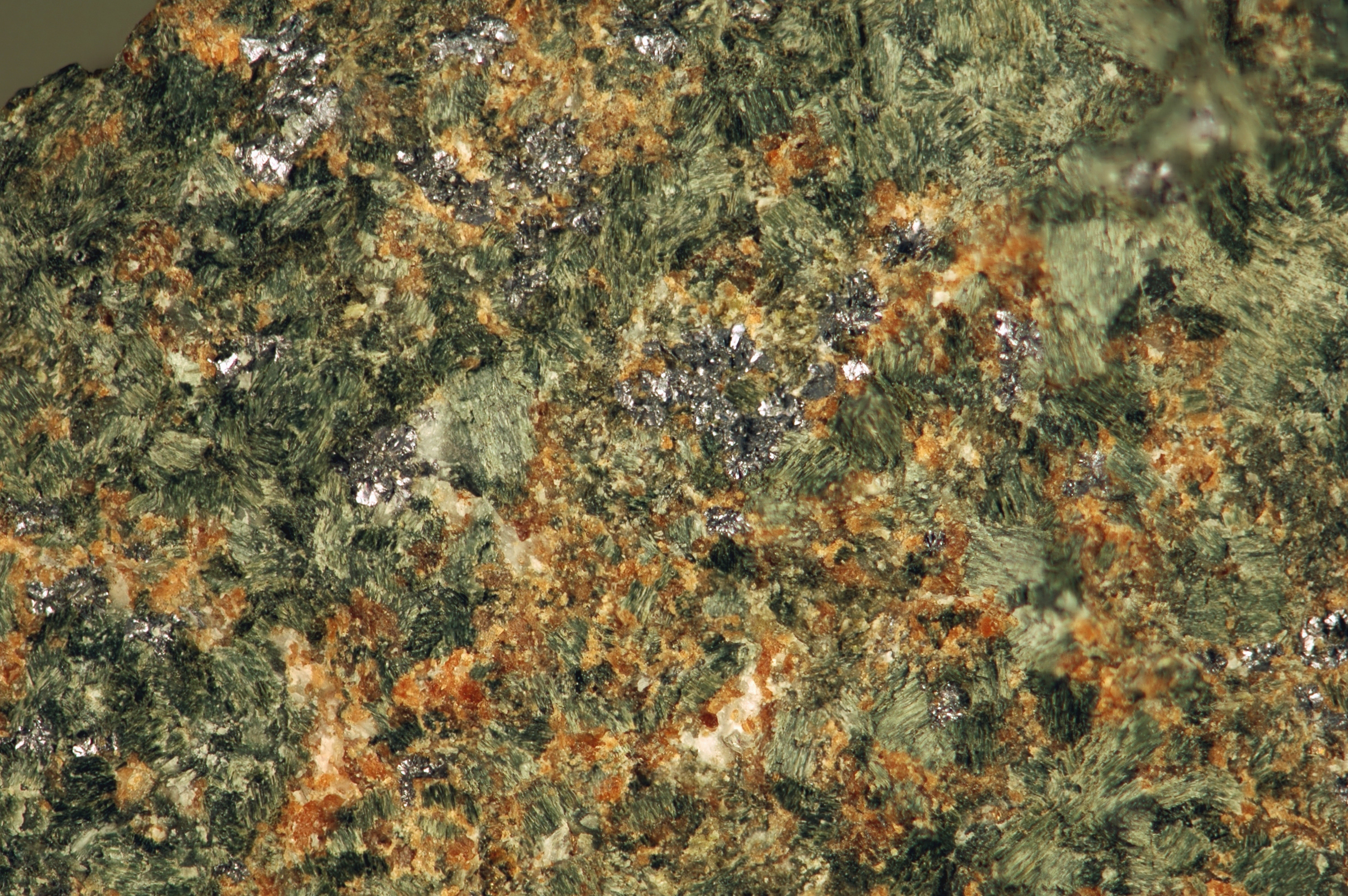

Deep-seated magma has a slow circulation of fluids, which are rich in copper, gold, silver, lead, and zinc. The magma doesn’t reach the surface; rather it slowly cools to form granitic rocks and circulates ore-bearing fluids. The metals originally disseminated throughout the magma are concentrated by circulating hot fluids and re-deposited to form veins.

The concentration occurs via:

- Gravitational setting

- Differentiation

- Immiscible separation of silica rich melt and a smaller volume of metal-rich liquid. This creates a wide variety of mineral deposits including:

- Metal oxides – hematite, ilmenite, iron, and titanium

- Sulfides – nickel, copper, platinum-group metals

- Carbonates – rare earth elements, niobium, tantalum, copper, thorium, phosphorous

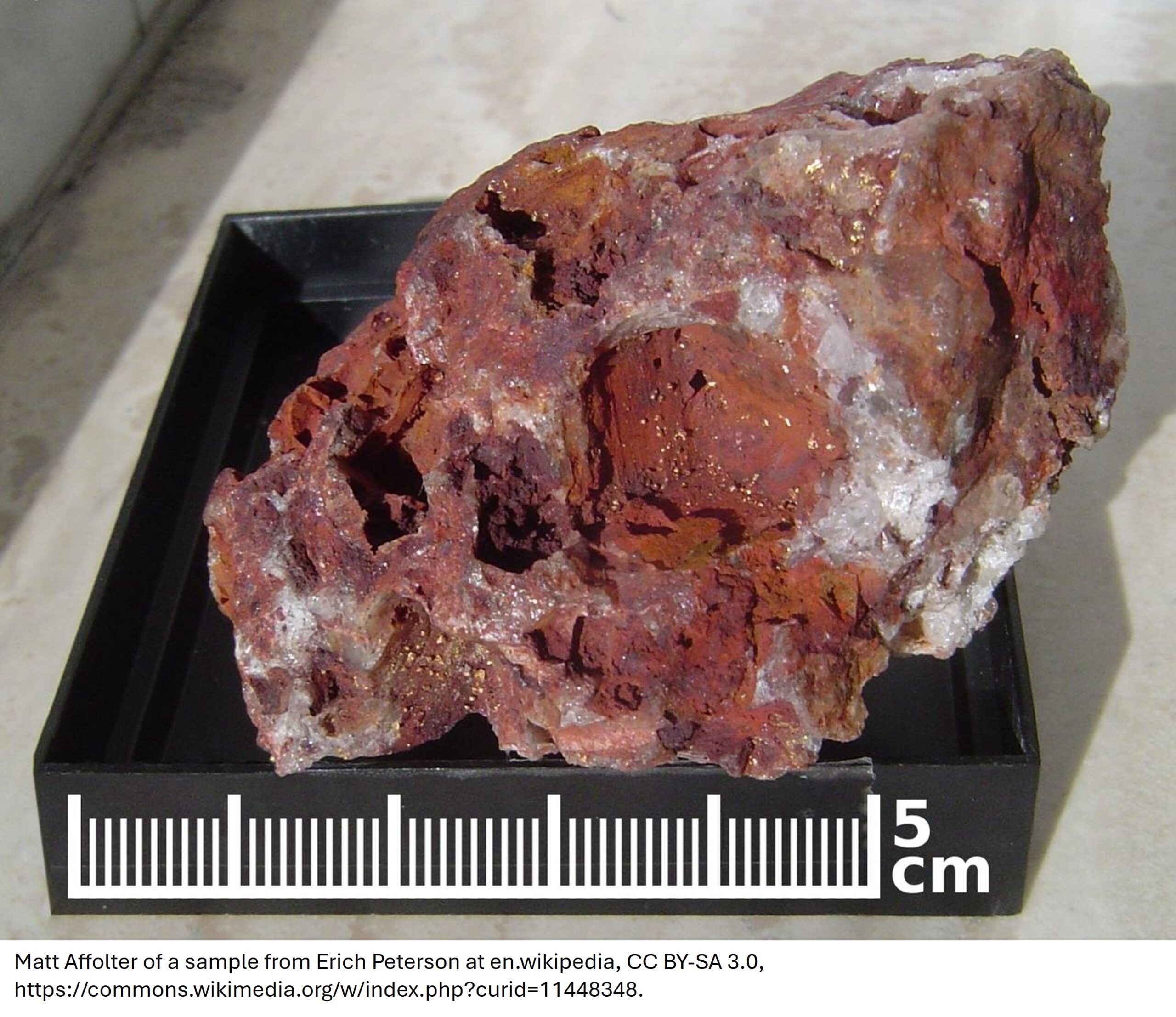

Sub-Sea Massive Sulfides

Vents along mid-ocean ridges create ideal environments for fluids rich in minerals to escape to the sea floor. Deep sea hot springs are rich in sulfides of iron, copper, zinc and nickel, and because of their black colour are known as black smokers. Troodos Massif, Cyprus, is an example of ancient oceanic crust, now uplifted and exposed on land. Troodos was an important source of copper to Romans, which they called “cyprium“. These deposits, known as volcanogenic massive sulphide deposits (VMS for short), are important sources of copper, zinc, lead, copper and silver.

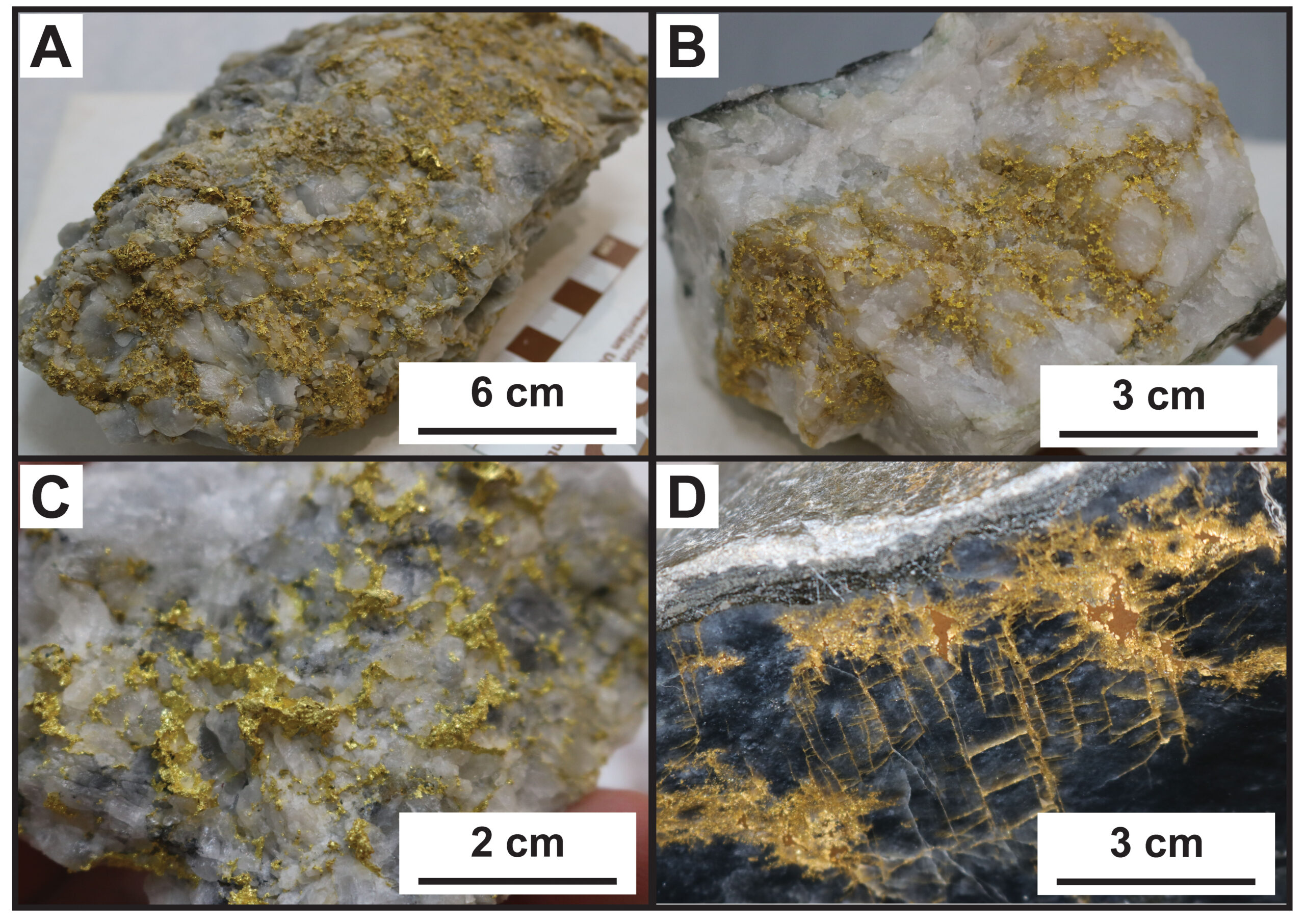

Gold Deposits

One of the characteristics that makes gold valuable is its resistance to reacting with other materials. It maintains its lustre because it does not react with the air and oxidize or rust. Gold does not mix well with fluids (think oil and water), but it can get carried long with them. This is why gold is often found as “free gold” in hydrothermal quartz veins or as free-gold in placer deposits. Depending on the hydrothermal fluid composition gold can also be trapped within the “matrix” of other minerals such as iron and arsenic sulfides. These micron-sized grains are difficult to extract from the sulfide ore.

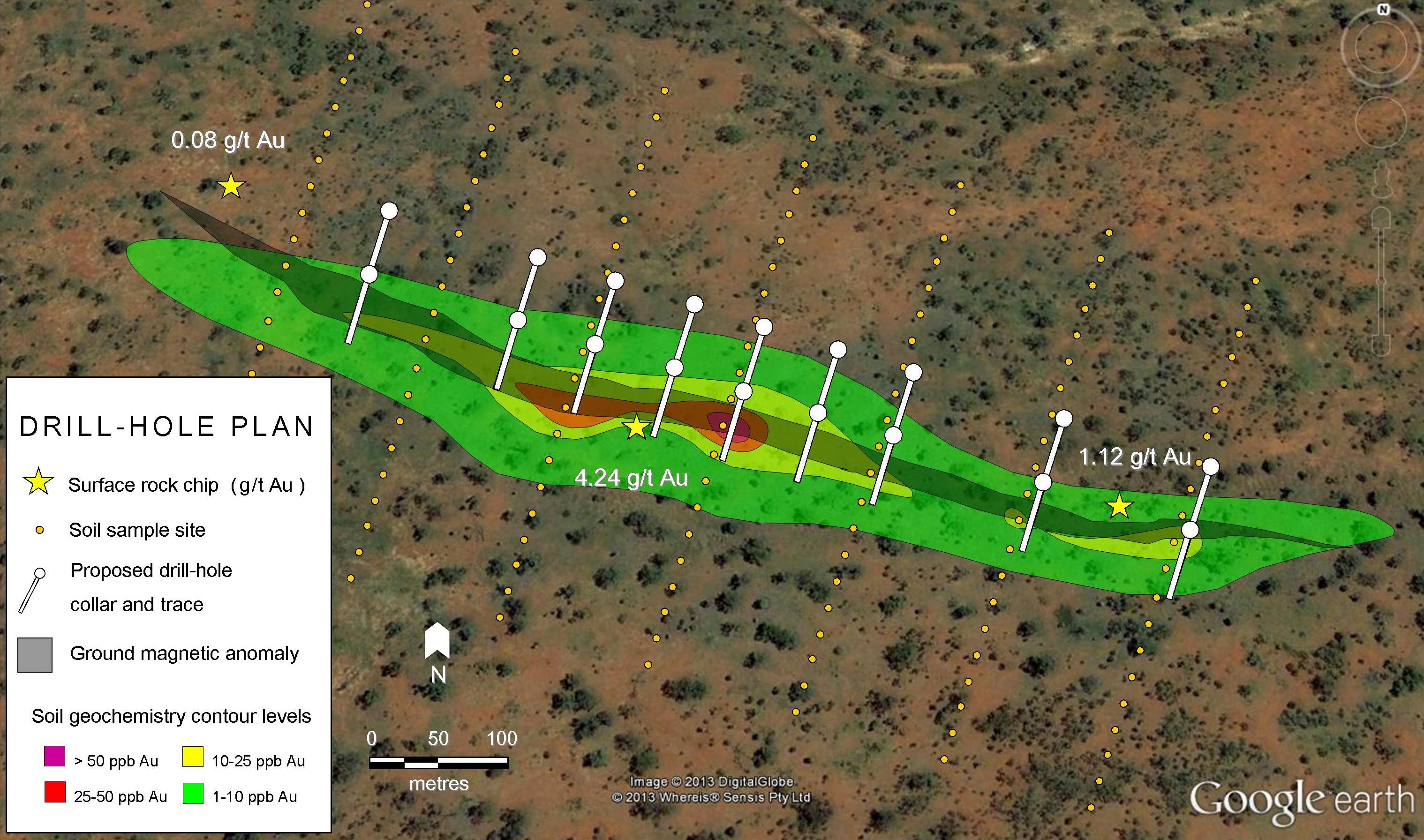

Since there is such a close association with hydrothermal activity and economic mineral deposits, geologists and prospectors will often look for signs of fluid and fluid saturation in rocks.