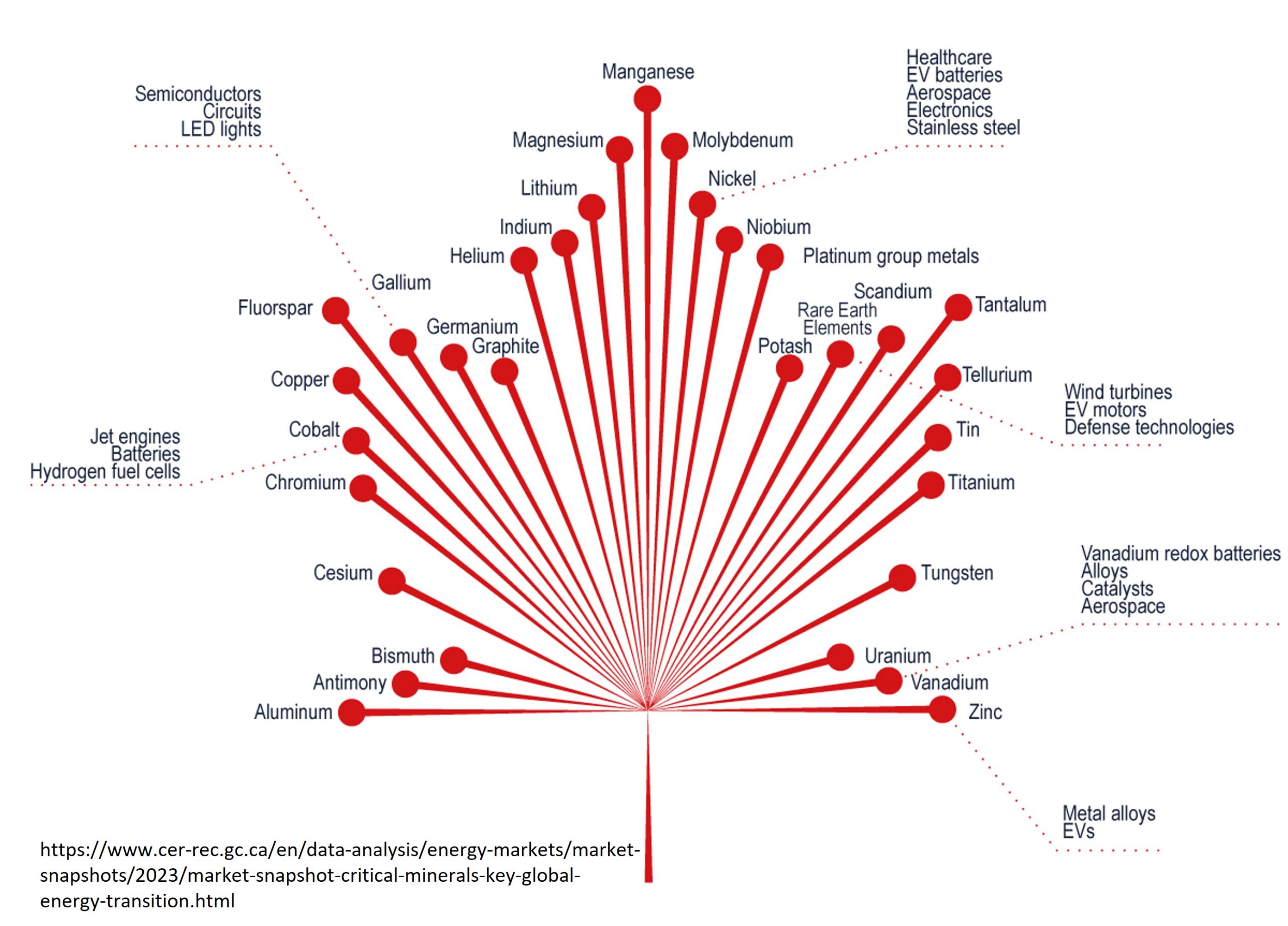

Unconventional sedimentary lithium resources have been under investigation since the 1970s by the US Geological Survey, various government agencies, and private companies. Despite ongoing research and development, these resources have not yet reached commercial production. However, such deposits are expected to play a crucial role in meeting long term demand projections, assuming these forecasts are accurate.

Lithium deposits can be classified into three types: brine, hard rock, and sedimentary. Currently, production is primarily sourced from South American salar brines, hard rock deposits in Western Australia, and various sources from China (Figure 1). Conventional brine extraction is cost effective, utilizing passive solar evaporation to concentrate lithium. Additionally, lithium is found in oil and geothermal brines, though these resources are still in the demonstration phase. Hard rock deposits, such as spodumene from pegmatites, are higher grade but are generally more expensive to process due to the need for drilling, blasting, and comminution (particle size reduction by crushing, grinding).

Deposit Occurrences

Sedimentary lithium deposits are located around the world including the United States, Mexico, Serbia, China, India, Peru, and Africa nations (figure 2). Most viable projects though are in the western United States in mostly favorable mining jurisdictions.

Many prospects are in Mexico with formation conditions similar to those of their northern neighbor. In 2021 Mexico nationalized lithium and in 2022 created the state company LITIOMX. Ganfeng’s Sonora Project filed requests for administrative review of their concessions. Meanwhile, in 2024 the Suprema Corte de Justicia (Supreme Court) denied concessions to Grupo Bararal in Chihuahua State.

The Serbian government reinstated the mining license for Rio Tinto’s Jadar Project though there is parliamentary debate on banning lithium mining. Sedimentary resources span across China with a large resource in Yunnan Province.

Genetic Models and Depositional Environments

Genetic models of lithium deposits are not fully understood, but several key ingredients are known to be required for their formation. These include a mineral source, a process to transport lithium and sediments, and a natural trap to concentrate and hold lithium in-situ. Lithium deposits are typically found in arid, endorheic basins, which are hydrologically closed regions where evaporation exceeds precipitation. These basins are situated in tectonically active areas, such as those with volcanic activity or ongoing extensional tectonics, active up to the Quaternary Period. The geological setting involves a valley floor that subsides via caldera formation or extensional basin tectonics, resulting in the creation of closed basins that are conducive to the accumulation of lithium rich sediments. These settings offer the necessary conditions for lithium to concentrate in substantial quantities over geological timescales.

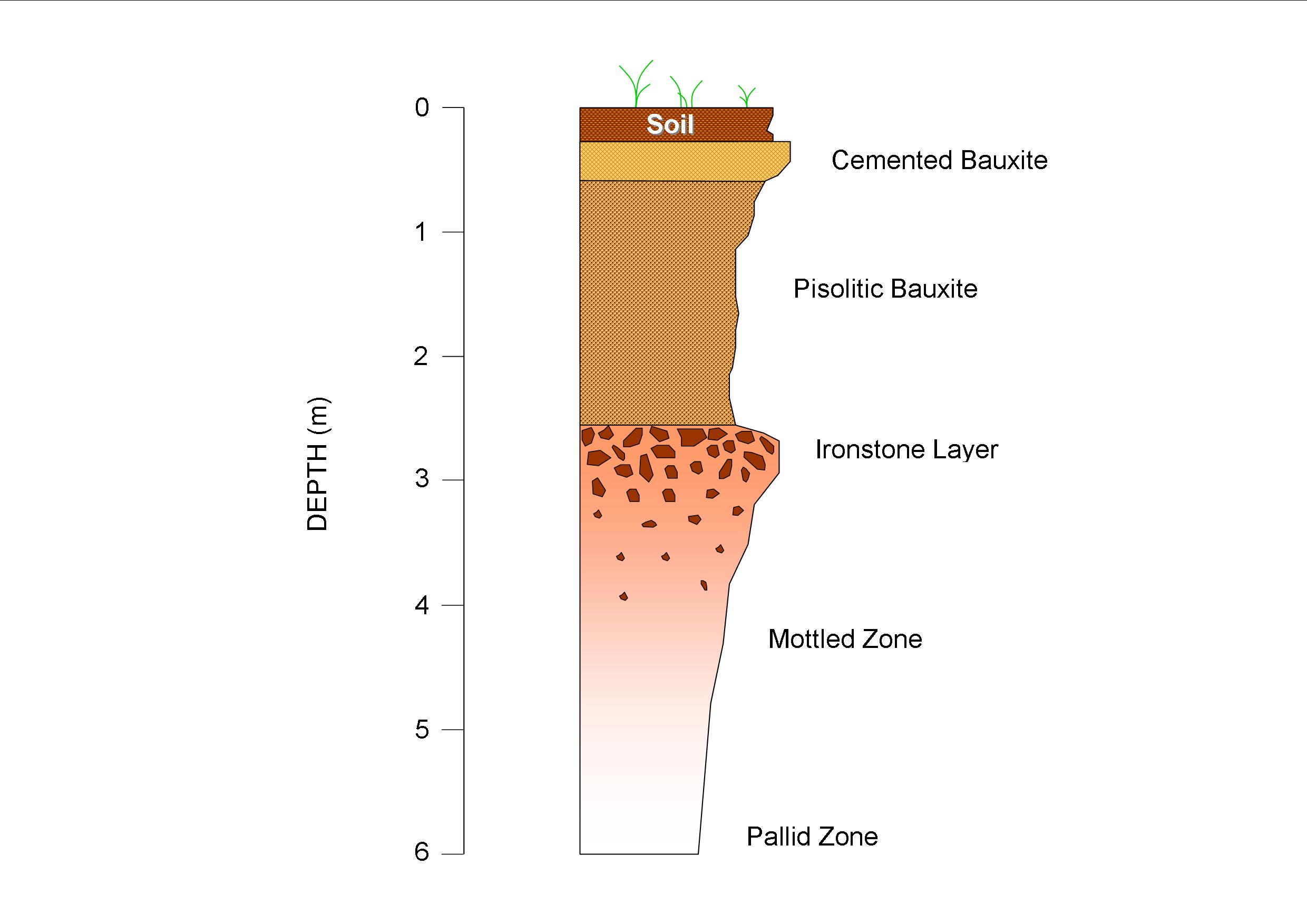

Lithium sources from the Cenozoic Era include rhyolitic magmatic fluids (figure 3), pyroclastic materials, high silica vitric volcanic rock (tuff composed mostly of volcanic glass fragments), ignimbrites (rock formed by ash flows), and lithium containing clay minerals. Structure is important as it facilitates the pathways for mineral transporting hydrothermal fluids while also physically constraining the size and shape of the basin. In some deposits, meteoric water facilitates sediment solution/dissolution kinetics.

Detrital material, derived from other rocks, is eroded from the mountains and carried into the valleys, filling the basins with sediments. In Nevada, these sediments can be up to five kilometers thick. Lacustrine (lake derived) sediment particle sizes range from clay, silt, and sand (<0.004, 0.004 – 0.06, and 0.06 – 2 mm diameter) where those in the basin bottom are finer grained and depending on conditions, host brine.

Mineralization

Mineralization occurs in tuffs (>75% volcanic ash content), evaporites, marls (clay and calcite), and in volcanic clays (figure 4). For example, jadarite is a lithium borosilicate evaporite that occurs in a low temperature, saline basin in Serbia. In Nevada, at Ioneer’s Rhyolite Ridge, lithium is found in both clay and marl, while in Clayton Valley, it is hosted in lacustrine sediments as wells as ash marker beds in the Esmeralda Formation.

Many sedimentary deposits are clay dominated, and therefore, the focus here is on clay. Clay refers to particle size and a clay mineral is defined as a naturally occurring inorganic compound with a crystal structure that forms with water. Clays belong to the phyllosilicate family of minerals and contain hydrous layer aluminosilicates comprised of silica, aluminum oxide, or magnesium oxide, with calcium, sodium, potassium, and iron. Lithium rich clays include smectite which usually contains the most abundant lithium, illite, chlorite, mica, and kaolinite. Non-lithium bearing clay minerals are vermiculite and halloysite. Smectite is formed from weathering of volcanic material. Hectorite, a notable smectite, was first discovered in Hector, California. Illite is formed by weathering and hydrothermal alteration. While smectite usually contains substantially more lithium than illite, at Lithium America’s Thacker Pass Project in Nevada, the lithium grades are twice that of smectites due to diagenesis from hydrothermal influence. Chlorite forms from the weathering of smectite and vermiculate and can contain cookeite.

Clay layers occur in tetrahedral and octahedral sheets bonded together by oxygen atoms with an interlayer allowing ion exchange and water movement. The silica ratio is key for clay mineralogy and for isomorphic substitution of lithium. Cation exchange capacity is a measure of the ability for the lithium ion to mobilize into the interlayer space and the specific surface area is that part of the clay mineral that can accept the ion. Smectite has high cation exchange capacity and specific surface area in relation to illite and chlorite.

Exploration

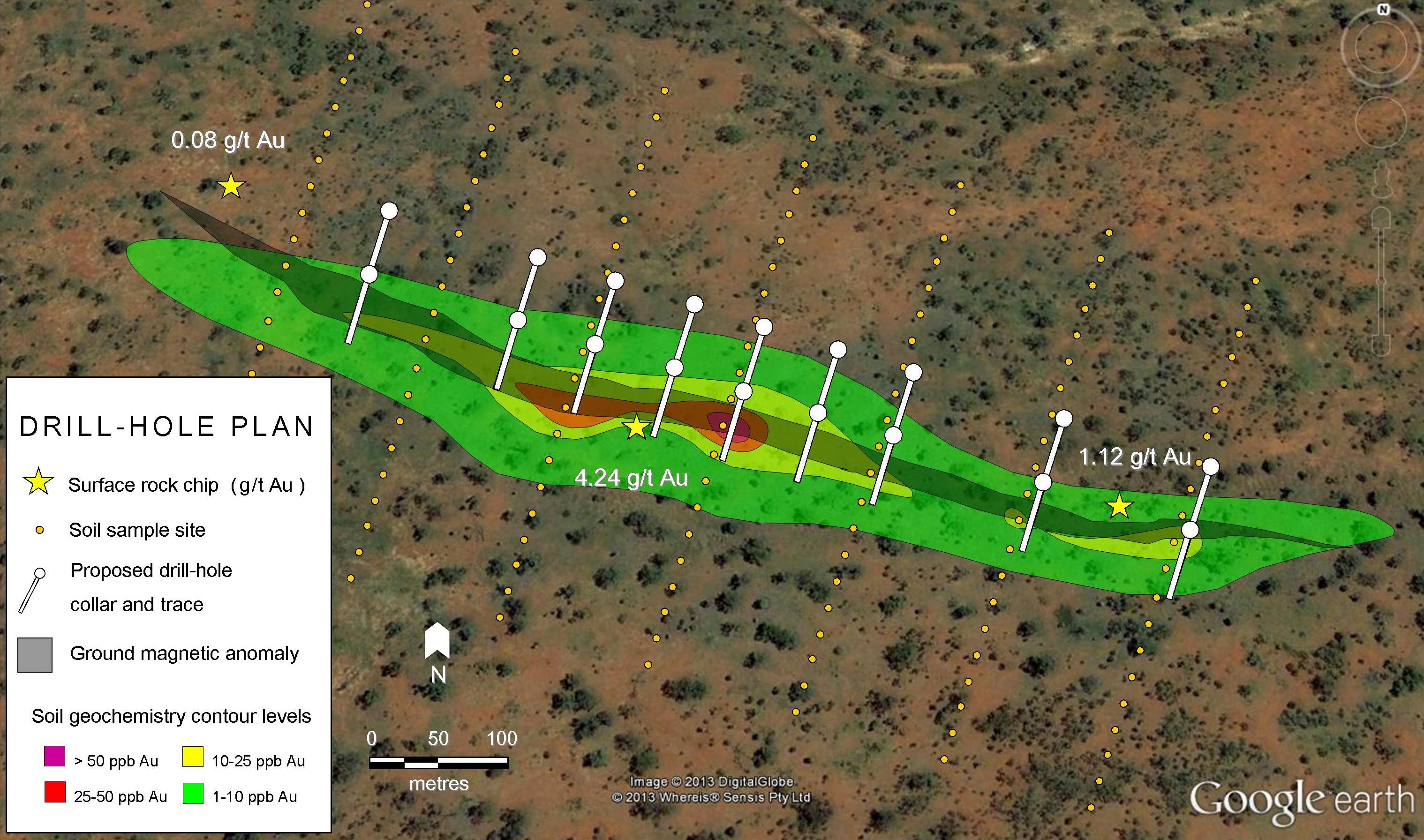

Remote sensing and surface geophysics include aerial photography, topography, airborne magnetics, magnetotellurics, gravity, and ground penetrating radar. Hyperspectral imaging has the ability to determine the difference between octahedral and tetrahedral clay structures. These surveys support geologic mapping and drill target identification.

Surface and float samples are collected to detect geological anomalies and can be geochemically screened using a handheld laser induced breakdown spectrometer (LIBS) tool. Geochemistry is confirmed by certified assay labs using a four acid digestion.

Drilling methods need to be appropriate for unconsolidated sedimentary material. They include reverse circulation, air core, diamond core (figure 5), and sonic. Proper sample collection is important for geochemical assays, lithology, and for density testing to support ore estimation. Useful downhole measurements include resistivity and conductivity, acoustic, spectral, and gamma ray logs.

Mining

Mining sedimentary deposits is generally simplified compared to other deposit types because they are large, often shallow, and flat lying with simple stratigraphy and can be mined by open pit. They contain high ore tonnage with minimal overburden resulting in low waste to ore strip ratios. Drilling and blasting typically is not required because most of the comminution and beneficiation was done by natural processes.

Some exceptions include Thacker Pass requiring minor drilling and blasting in a small pit zone, Bonnie Claire proposing a combination of open pit and borehole mining (in-situ leaching), and Jadar that is planned as an underground mine.

Run of mine ore is generally 0.2 – 1.5% Li2O with impurities. Ore concentration is necessary where flotation and centrifugal concentrators are utilized. Sometimes beneficiation like fine grinding is required. Clays have high porosity and low permeability making solid-liquid separation, filtration, and tailings handling challenging.

Host sediment and mineralogy are key for determining project feasibility because of the complex metallurgy. Processing is rapid (hours) and overall recovery is close to 80% on average for sediment resources (as listed in company reports) compared to around 60% for hard rock and around 40% for conventional brine. The end product, usually lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide, and whether battery or industrial grade, dictates the bespoke flowsheets utilized.

Tetrahedral structure is destroyed by acid leaching and octahedral structure can require high acid use or roasting / calcination (heating to decompose carbonates) (figure 6). The structural position of magnesium and potassium ions is important for lithium leachability. Deposits with lithium in the interlayer are rare. The most common extraction method uses sulfuric acid leaching utilizing vats, heaps, or in-situ, and acid recycling reduces costs and minimizes waste.

Other leaching mediums use hydrochloric acid, chlor-alkali (Century Lithium), and sulfate. Other extraction methods include water disaggregation, hydrothermal treatment, electrical separation, and mechanochemistry. Tesla’s patent describes mechanochemistry comprised of high energy milling with addition of the catalyst sodium chloride.

Lithium carbonate is precipitated out using soda ash and various processes are used to convert to lithium hydroxide. Deleterious elements are removed using calcium and sodium carbonate and via evaporation, crystallization, and ion exchange.

Operating and Capital Expenditures

The range of operating expenditures for sedimentary resources lie between low cost brine and higher cost hard rock producers. Of the sedimentary projects examined, operating cost was between $2,510 to $17,000 per tonne lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) but most projects were less than $8,000. Projects on the lower end of the cost curve have by-products that enhance the economics (American Lithium – magnesium sulfate, Century Lithium – sodium hydroxide, Ganfeng – potassium sulfate, Ioneer – boric acid, and Nevada Lithium – boron). In general, higher grades should be more efficient to process.

Higher mine production rates require higher capital expenditures, as would be expected. However, the type of processing plant being built does not have a dramatic effect on cost.

Risks

Lithium price volatility is evident in this emerging market, creating opportunities for contrarian investors to achieve substantial profits. Government efforts to decarbonize are a key driver of lithium demand. However, the impact of the 2025 United States presidential administration will take time to manifest, as there are plans to dismantle the Inflation Reduction Act, deregulate carbon emission standards, and eliminate incentives for electric vehicles. Currently, most viable sedimentary lithium projects are located in the western United States. Although these deposits have yet to be produced at a commercial scale, long term global demand for lithium is still projected to rise dramatically that will require all lithium sources.

Companies Mentioned

- American Lithium Corp.: https://americanlithiumcorp.com/

- Century Lithium Corp.: https://centurylithium.com/

- Ganfeng Lithium Croup Co., Ltd.: https://www.ganfenglithium.com/index_en.html

- Ioneer USA Corp.: https://www.ioneer.com/

- Litio Para México: https://www.gob.mx/litiomx

- Lithium Americas Corp.: https://www.lithiumamericas.com/

- Nevada Lithium Resources Inc.: https://nevadalithium.com/

- Rio Tinto PLC: https://www.riotinto.com/en/operations/projects/jadar

Further Reading

- Benson, T., M. Coble, and J. Dilles. 2023. Hydrothermal enrichment of lithium in intracaldera illite-bearing claystones. Science Advances, 9, 35, p 1-10.

- Coffey, D., L. Munk, D. Ibarra, K. Butler, D. Boutt, and J. Jenckes. 2021. Lithium storage and release from lacustrine sediments: Implications for lithium enrichment and sustainability in continental brines. Geophysics, Geochemistry, Geosystems, 22, p 1-22.

- Scott, J., L. Buatois, and M. Gabriela Mángano. 2012. Chapter 13 – Lacustrine Environments. In Developments in Sedimentology, 64, p 379-417.

- Tourtelot, H. and E. Brenner-Tourtelot. 1978. Lithium, a preliminary survey of its mineral occurrence in flint clay and related rock types in the United States. Energy, 3, 3, p. 263-272.

- Xie, R., Z. Zhoa, X. Tong, X. Xie, Q. Song, and P. Fan. 2024. Review of the research on the development and utilization of clay-type lithium resources. Particuology, 87, p. 46-53.

Zhoa, H., Y. Wang, and H. Cheng. 2023. Recent advances in lithium extraction from lithium-bearing clay minerals. Hydrometallurgy, 217, 106025.