The Morenci Copper Mine: 148 Years and Counting

Most mines are lucky to last more than a decade or two. After nearly 150 years of production, Arizona’s Morenci copper mine, the largest Copper producer in North America, isn’t even thinking about closing.

Project Overview

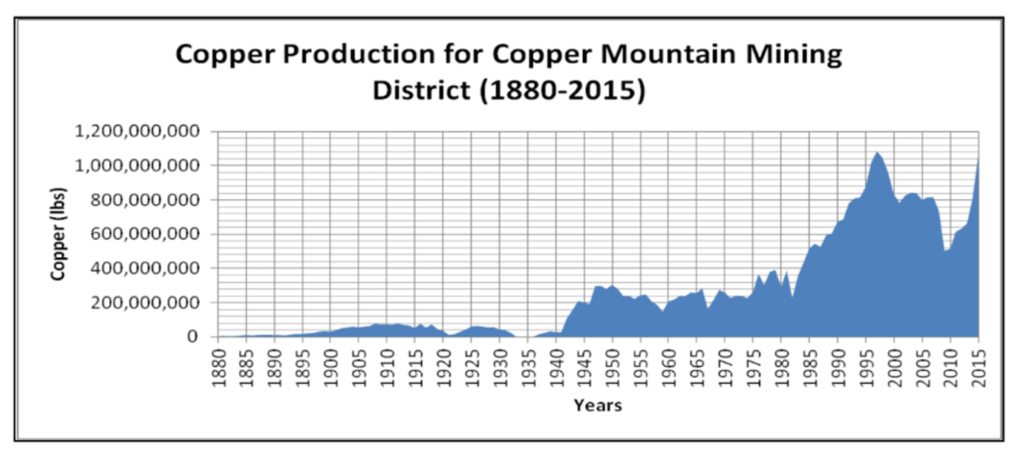

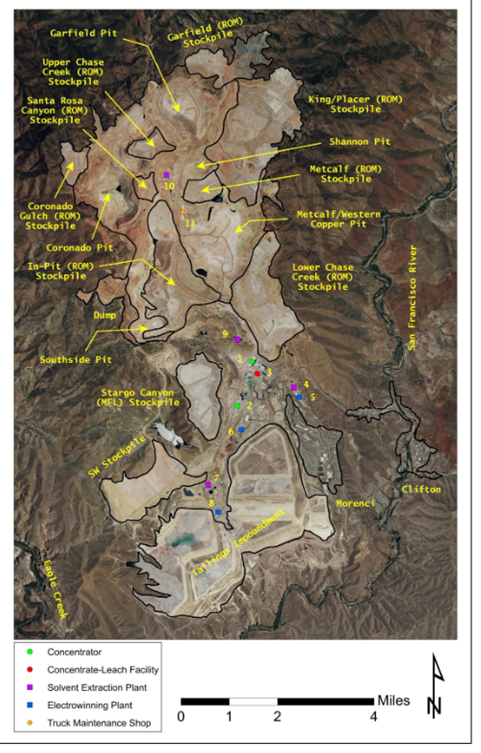

With Copper (Cu) production beginning in 1873 and continuous since 1939, Morenci (AKA Copper Mountain) is one of the largest and oldest Cu mines in the world. As of December, 2015, Morenci’s ore reserves stood at ~3.9 billion tons at ~0.27% Cu, with resources of ~1.7 billion tons at ~0.24% Cu. Most of these reserves are in the form of low grade (0.18%) ore which is processed via heap leaching. Higher grade (~0.42%) ore is processed via a new, high-efficiency mill, which also recovers molybdenum (Mo) at a grade of ~0.02% Mo. Combined reserves and resources contained ~29 billion lbs Cu and ~0.6 billion lbs Mo, which is enough to extend mine life through at least 2038.

The Morenci Project is 72% owned by Freeport-McMoRan, inc., with Sumitomo Metal Mining Co. Ltd. owning 25%, and Sumitomo Corporation holding the remaining 3%. For over a decade Freeport has carried out ambitious expansion plans at the several large copper-gold-molybdenum mines it owns in the U.S., South America, and Indonesia. Since it acquired a controlling interest in 2007, Freeport has invested billions into an aggressive program to expand both reserves and production at Morenci. These investments have borne fruit, with billions of pounds of Cu added to reserves and a mill expansion project completed in 2015 increasing production from 50,000 to approximately 115,000 metric tons of ore per day. Annual Cu production has increased by about 225 million pounds per year, making Morenci the largest Cu producer in North America. Most of its production is used domestically.

Geology

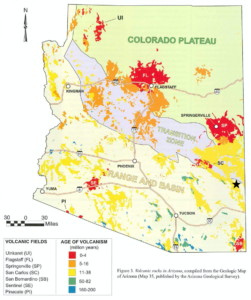

The Morenci deposit is hosted with in the basin-and-range province of the U.S. southwest, an area where the Earth’s crust is being stretched and pulled apart by tectonic forces. This stretching leads to the development of large blocks separated by faults. As is often the case, these faults provide pathways for ore-forming fluids to migrate towards the surface, while the movement of the blocks helps bring deposits formed at great depth towards the surface. This geology makes the region highly favorable for the formation of porphyry Cu deposits, of which Morenci is just one of many.

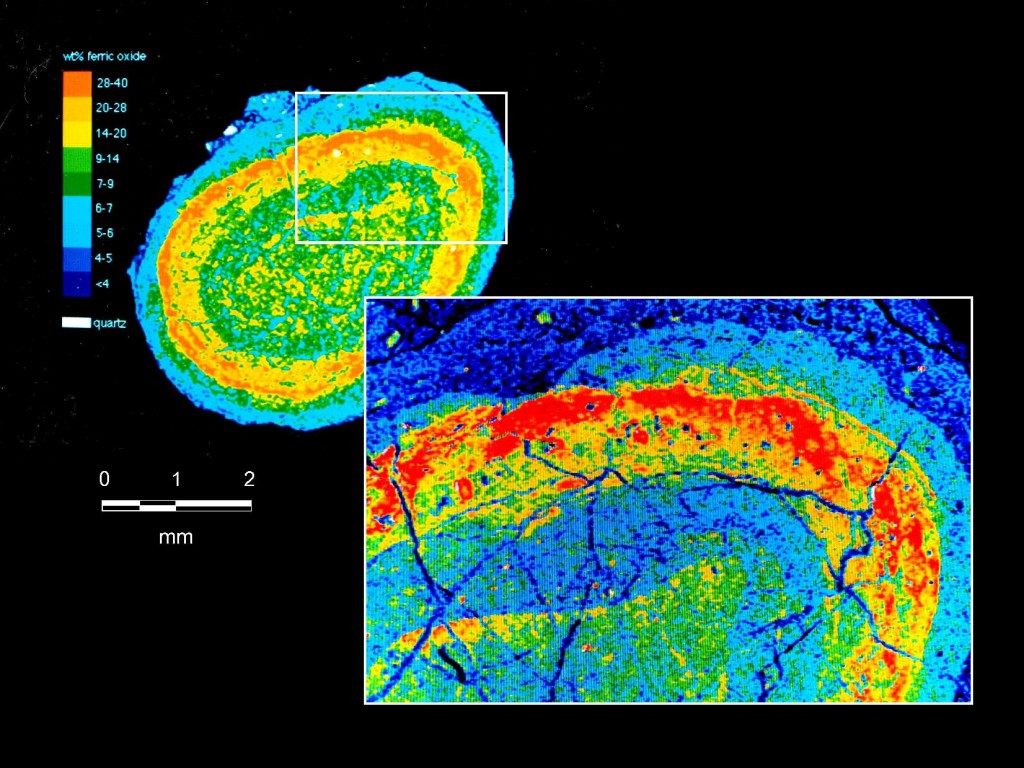

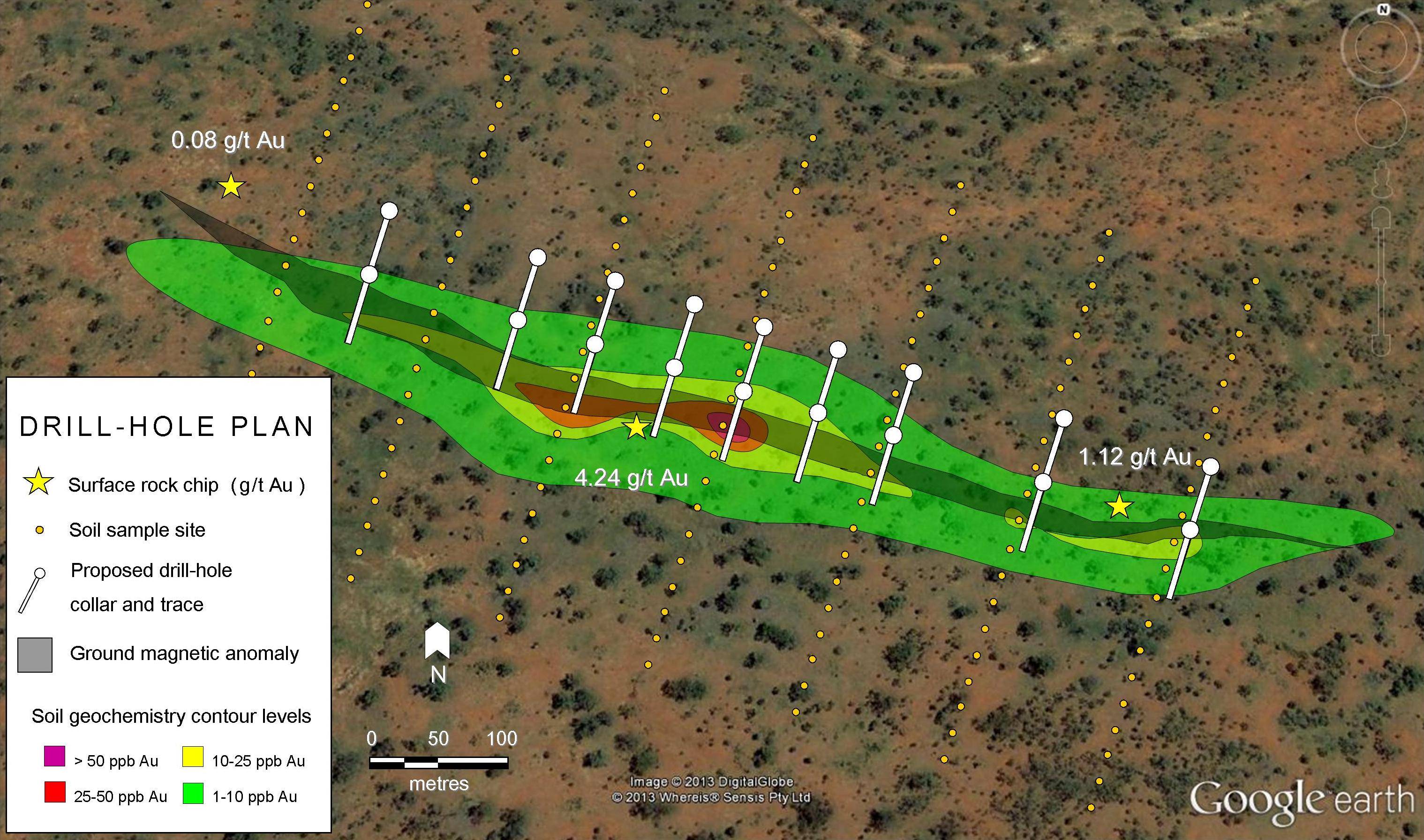

Porphyry deposits form as a result of deep-seated granitic intrusions releasing hot, metal-rich fluids as they solidify. These fluids form nested shells of progressively lower temperature potassic-sericitic-propylitic alteration as well as quartz veining around the source intrusion. Porphyry deposits tend to be low-grade, and large tonnage, with ore consisting of disseminated (dispersed) Cu and Mo sulfides, often with lesser amounts of gold and silver.

In many ways Morenci is a typical porphyry deposit, although it is somewhat unusual in that its main ore mineral is chalcocite, and in that it contains relatively little precious metals. Chalcopyrite is the primary Cu sulfide ore mineral; however much of this Cu has been modified into secondary, and more Cu-rich, sulfides such as chalcocite as well as oxide minerals such as chrysocolla. Although Morenci does not produce gold or silver, some Mo is extracted from molybdenite.

A Rich History

The history of Morenci is one of decreasing ore grade more than offset by increasing scale and technological innovation. Although strikingly-coloured Cu minerals have long been used by the area’s indigenous inhabitants, commercial Cu production began at Morenci in 1873. Production, made possible by newfound peace with the Apache tribes, was initially from primitive pick-and-shovel operations mining small zones of secondary enrichment, where weathering had created Cu oxide and carbonate minerals with grades as high as 20% Cu. These rich ores were quickly exhausted and by the 1890’s miners, aided by new and more efficient ore concentrators and smelters, were mining lower-grade Cu sulfide minerals from underground shafts.

Over the next few decades grades slowly decreased to around 2% Cu, but production continued to rise as small claims were consolidated into a larger, more efficient operations under companies such as Phelps, Dodge and Company, Inc. Several of these companies constructed elaborate railroad networks to better transport ore through the region’s mountainous terrain.

The Great Depression hit Morenci hard, forcing underground operations to cease in 1932. By 1937 rising Cu prices spurred Phelps Dodge to redevelop Morenci as an open pit, with ore grading ~1% Cu loaded onto ore trucks by enormous electric shovels for transport to a new, much improved, concentrator and smelter. This new operation began production in 1942, just in time to supply Cu for the war effort, which was in such short supply that the military actually resorted to raiding the U.S. treasury for silver, which it substituted for the suddenly scarce Cu needed for the Manhattan Project. Despite several major labor disputes and strikes, Morenci largely prospered during the post-war years and decades. By the 1980s low Cu prices and the inability of Morenci’s smelter to meet new environmental regulations could have spelled doom but instead led to the construction of a new hydrometallurgical plant as well as the use of heap-leaching to process ore which had previously been too low-grade to profitably mine. This, along with the discovery of new ore bodies, allowed Morenci to continue and even expand production even as the original open pit was mined out and ore grades continued to decline.

Freeport-McMoRan Copper and Gold, Inc. (since renamed Freeport-McMoRan, Inc.) acquired an 85% interest in Morenci when it merged with Phelps Dodge in 2007. Between 2012-2015 Freeport-McMoRan invested over $10 billion in major expansions at several of its mines, including Morenci. This expense, combined with other acquisitions and falling commodity prices, prompted Freeport-McMoRan to sell a 13% interest in the Morenci project to Sumitomo Metal Mining Company for $1.0 billion in 2016.

Investor Takeaways

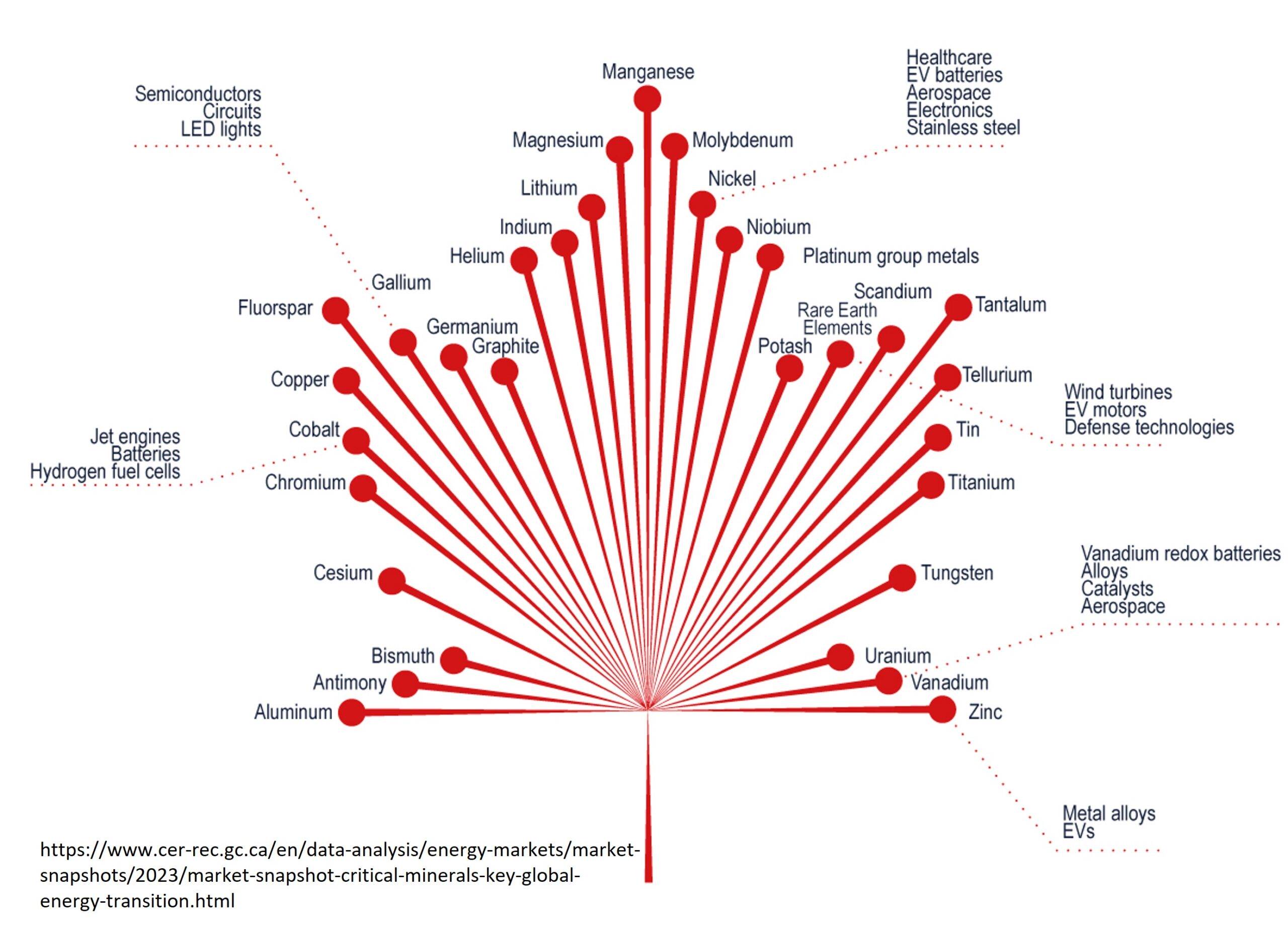

To say Freeport McMoRan is all in on Cu would be an understatement. The company is focused almost exclusively on large Cu porphyry deposits, which, as the history of Morenci illustrates, have the potential to be very large, long-term, and relatively stable producers. The strategy of expanding such operations has required significant capital investment but has allowed Freeport to increase production relatively quickly by avoiding the often lengthy and politically fraught process of opening a new mine. Major expansion projects are either complete or well underway at Morenci and Safford/Lone Star mines in Arizona, Grasberg in Indonesia, and Cerro Verde in Peru, are being evaluated at El Abra, Peru, and may soon be coming to at least three more operations in the U.S. Cumulatively, the reserves of Freeport McMoRan’s projects total 113.2 billion lbs Cu, 3.7 billion lbs Mo, 29 million ozs gold, and 362 million ozs of silver.

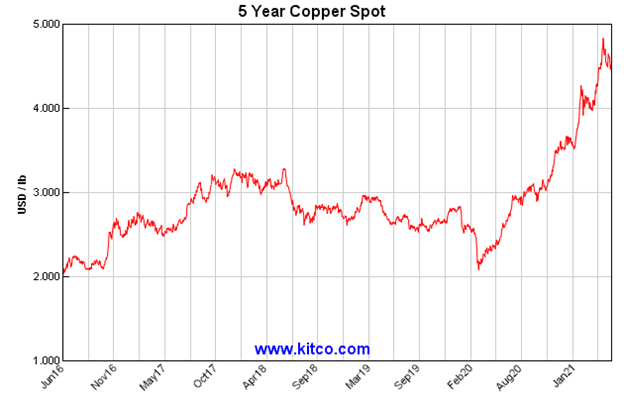

This aggressive expansion appears well-timed. Although Freeport’s lack of diversity leaves it exposed to drops in Cu prices, the indispensability of Cu in all things electronic points to Cu being a good long-term bet. Beside numerous applications in manufacturing and construction, electric vehicles, green energy, and power grid expansion projects (all featured heavily in Biden’s infrastructure plan) all require large amounts of the red metal, which is part of the reason Cu prices have doubled over the last year. This has directly translated to a doubling of Freeport’s stock price. The company is now worth more than Barrick, which just last year was floating the idea of buying Freeport, which at the time was struggling to continue operating due to weakened Cu demand and Covid-19 related challenges.

Whether or not Cu prices remain at historic highs, demand will almost certainly remain high in the long run. With its’ strong history of continuous production, yet another major expansion complete, and ore for decades to come, Morenci’s future seems bright as it approaches its 150th year.

List of Companies Mentioned

- Freeport-McMoRan Inc. (website)

- Sumitomo Metal Mining Co. Ltd. (website)

- Sumitomo Corporation (website)

Resources

- Briggs, D.F. (2016): History of the Copper Mountain (Morenci) Mining District, Greenlee County, Arizona. Retrieved from: website

- Freeport-McMoRan (2021): Morenci. Retrieved from: website

- Schyeder, E. (2021): Freeport eyes U.S. expansions as Biden’s EV plan boosts copper demand. Reuters. Retrieved from: news article

References

- Briggs, D.F. (2016): History of the Copper Mountain (Morenci) Mining District, Greenlee County, Arizona. Retrieved from: website

- Freeport-McMoRan Inc. (2020): Freeport-McMoRan 2020 Annual Report. (pdf)

- Freeport-McMoRan (2021): Morenci. Retrieved from: website

- Kitco.com (2021): 3 year copper spot price. Retrieved from: website

- Schyeder, E. (2021): Freeport eyes U.S. expansions as Biden’s EV plan boosts copper demand. Reuters. Retrieved from: news article

- St. John, J. (2013). Wikipedia. Retrieved from: website

Subscribe for Email Updates